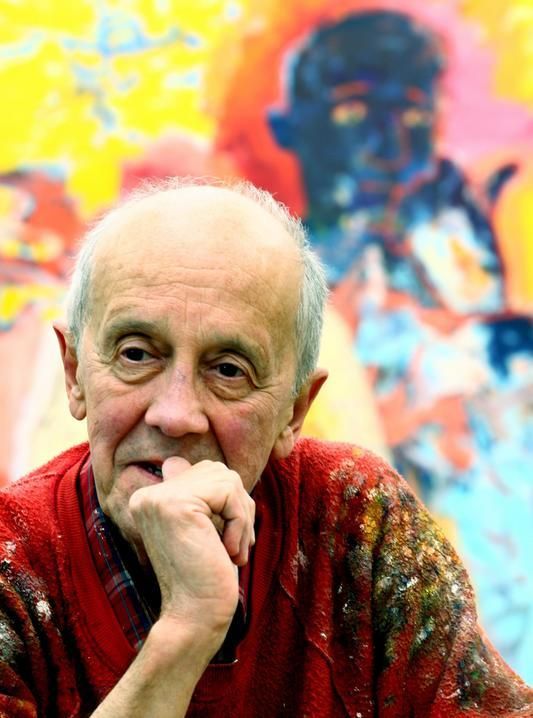

Philip Morsberger (1933-2021)

With the death of Philip Morsberger on Sunday, January 3, 2021, of complications due to COVID, “Augusta and America have lost a giant among artists,” as Morris Museum founder William S. Morris III has said. “We were fortunate to recruit him to Augusta State University as the Morris Eminent Scholar—more fortunate still that he chose to make Augusta his home for the rest of his remarkably productive life. His gifts to the community are numerous, but perhaps the greatest of them was his presence and the shining example he provided of the creative life.”

He was born in Baltimore in 1933, he son of Eustis Espey Morsberger, a printer and newspaperman, and Mary Burgess Morsberger, a teacher. (His loyalty to his boyhood home was signaled by his always flying the state flag of Maryland at his home.) More than 20 years ago, he and his wife Mary Ann moved to Augusta, when he was named the Morris Eminent Scholar in the Visual Arts at Augusta State University. He discovered the magic of art as a child, when he found himself dazzled by his grandfather’s ability to change illustrations in the daily newspaper with the aid of a pencil. From that time until the end of his life, he looked on art as something alchemical. He drew at home under his grandfather’s tutelage, and as soon as he could he commenced formal study at the Maryland Institute College of Art. (He was not yet 14 at the time.) He earned a BFA from Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University) where he met the young woman who became his wife. (Mary Ann Gallien was also a graduate of the class of 1954.) After service in the U. S. Army that took him to Paris, where he studied in his off-duty hours at L’Académie de la Grande Chaumiėre, he attended Oxford University’s Ruskin School of Drawing on the G.I. Bill. There, he earned a graduate certificate in fine arts. So armed, he returned to the United States with his wife and young daughter before embarking on a singularly successful and unusually peripatetic teaching career that included appointments at the Rochester Institute of Technology, the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University, and Dartmouth College, before returning to the Ruskin School where he served as Master of Drawing for 13 years. During his tenure at Oxford, he led the growth of a program into a full-staffed, degree-granting department On his second return to the United States, he held appointments at the University of California, Berkeley, the San Francisco Art Institute, and the California College of Arts and Crafts. On his retirement from CCAC in 1996, he was named the second Morris Eminent Scholar, a position he held for five years before retiring again. He remained in Augusta ever after, actively creating new works of art until the last week of his life. Throughout their travels, the Morsbergers were famous for their hospitality, welcoming all and sundry into their homes in the United States and Great Britain and hosting parties that are now the stuff of legend.

His work, like the man himself, is inimitable. He studied at Carnegie Institute at a time when Abstract Expressionism was in the ascendant, but he didn’t much care for it, preferring instead the work of such Bay Area figurative painters as Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn, and Nathan Oliveira. The training in the classic academic style that he later received at the Ruskin School was more to his liking. Through the 1960s, he remained a committed realist, treating such events as the Kennedy assassination, the Civil Rights Movement, and the other divisive political issues of the day with an almost reportorial precision, but by the early 1970s he’d done all he could in that vein and turned to the creation of highly expressive abstracted landscapes. Ten years later, he came to acknowledge that he missed the figure and began to develop the cartoon-like style for which he is now chiefly known. His deft drawing, fabulous sense of color, and use of a repeated cast of characters—many of them drawn from memories of his childhood—enabled him to create a running commentary on a world that appeared to him to have grown absurd. Art historian Christopher Lloyd observed that his paintings deal with “universal truths about life and death through a sequence of personal references.” Morsberger himself said, “All these paintings are on their face comedic, but they are a little bit like whistling in the cemetery. They are about life, death, and resurrection.”

Sandra Rupp, whose Hampton III Gallery represented Morsberger for more than twenty years, said that “he helped us all see what we could not. By opening his life, he revealed our own. Often quirky, other times funny and sometimes sad, he took us to a better place through his art.”

His work is included in the permanent collections of many museums, including Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum and the South Hampton City Art Gallery in England; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the San Jose Museum of Art and Sacramento’s Crocker Art Museum in California; the Morris Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art Atlanta in Georgia; the Columbus Museum of Art and Youngstown’s Butler Institute of American Art in Ohio; the Rochester Memorial Art Gallery in New York state; Dartmouth’s Hood Museum in New Hampshire; and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans. He has exhibited widely in the United States and Europe. At the time of his death, he was represented by Hampton III Gallery in Greenville and IF Art Gallery in Columbia, South Carolina; Out of the Box Fine Arts in Augusta, Georgia; and Harmon-Meek Gallery in Naples, Florida.

His life and work were the subject of Philip Morsberger: A Passion for Painting (2007) by Christopher Lloyd. He and his work also were the subject of or included in many other books and catalogues, including Susan Landauer’s The Lighter Side of Bay Area Figuration (2000), J. Richard Gruber’s Philip Morsberger: Paintings and Drawings from the Sixties (2000) and Marcia Tanner’s Philip Morsberger (1992), as well as the documentary film Motivated by Color: The Life and Art of Philip Morsberger.

Painter Brian Rutenberg said of him, “Like all great artists, Philip was interested in everything; less than that was a ‘betrayal of the intellect’, he told me. When we were together, whether over dinner, in his studio, or in our letters, Philip never spoke directly about painting but about the painter’s life. Truly the sign of a mentor. He said that painting was a form of prayer, less about ‘getting it right’ than about unfulfilled longing. This is why everyone of his canvases is a compressed version of the joy, sorrow, and wonderful strangeness of a life lived.

My favorite memory with Philip was a lazy summer evening in his Augusta studio listening to chamber music and talking about poets, specifically Robert Frost. This line from A Servant to Servants came to mind upon learning of Philip’s passing:

‘He says that the best way out is always through.

And I agree to that, or in so far

As that I can see no way out but through.’”

He is survived by his daughter Wendy Morsberger (Gareth Hougham) of Ossining, New York; his companion, sculptor Anita Huffington; niece Grace Morsberger (Richard Stern) of Vienna, Austria; three grandsons (Ben, Jesse, and Elan Morsberger); a great-niece and great-nephew (Emma and Jake Stern); as well as countless Morsberger cousins in and around Catonsville, Maryland. He was preceded in death by his wife of 64 years, Mary Ann Gallien Morsberger, and his son Robert Edward Morsberger (Lisa Morsberger), a prominent film and television composer and singer/songwriter, and his brother Robert Eustis Morsberger, a retired professor in the English department at California Polytechnic State University and a respected biographer.

A memorial service will be scheduled at a later date. In lieu of flowers, the family requests that his friends and admirers make a donation to the Philip Morsberger Fund at the Morris Museum of Art or to the Philip Morsberger Fund at Augusta University’s Department of Art + Design.